Dialogue with the Dean and Ruha Benjamin: Technology’s Race Problem

Images, said Ruha Benjamin, matter.

When the Princeton University professor of African American Studies was 11 years old, she determined her future was in the academy—due in large part to a passing appearance of the character Dean Hughes, the head of a fictional HBCU Hillman College, on the sitcom A Different World.

Access to—and autonomy from—technology, she learned, also matter.

At age 15, Benjamin and her family moved from South Carolina to the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific. There she noticed stark differences between one island’s incongruously suburban conveniences, thanks to its U.S. military presence, and a nearby island’s displaced indigenous population living with the fallout of sustained nuclear bomb tests.

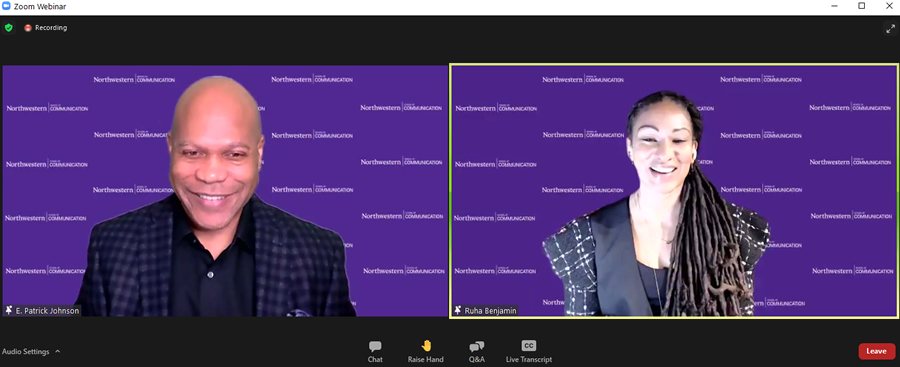

These early experiences shaped Benjamin’s approach to scholarship, a journey the author of Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code detailed during the 90-minute “Dialogue with the Dean” virtual speaker series on February 18. Hosted by School of Communication Dean E. Patrick Johnson, the series spotlights communication scholars advancing the futures of their fields, challenging paradigms, and promoting social justice. Benjamin’s work examines the social dimensions of science, technology, and medicine—in particular, who pays the price of tech’s big promise.

“It’s not simply the technology that is creating the problem. It’s what’s imbued in the technology,” Benjamin said. “It’s the values and the norms and the hierarchies that are encoded in it. One example is in a lot of the forms we have to fill out online. They’ll give you a certain amount of space to give a certain number of characters for your name. Some people come from a family or a culture that has a lot of characters.

“For example, my middle name is my mother’s maiden name. And there are a lot of cultures where your name isn’t just you, personally, but it’s also your lineage. So if you have too many names, or your name is too long, then whoever designed the little form is normalizing certain kinds of naming rituals. It’s creating a context where some names are legible—literally—and some names are not. So, that tells us if something like a simple-looking form that we don’t consider a cultural object, if that form has all of those decisions and values, then what about more complex technologies? How are they mediating whether it’s about race or gender or disability?”

Technology, the interlocutors agreed, isn’t confined to emerging automated systems and AI. The cotton gin and the metal pen tip, Johnson noted, were considered revolutionary but at the expense of Black labor and literacy. And now more modern devices, sold on the promise of ease, liberation, and inevitability, are imbued with algorithmic bias.

“I tell you, me and Alexa, we don’t get along. We are not friends because she hurts my feelings all the time,” Johnson said of Amazon’s digital assistant. “She can’t understand what I’m saying sometimes. I know that for instance, Alexa will understand, ‘Alexa, will you turn off the lights?’ But, Alexa may not understand, ‘Alexa, cut that light out.’ And Siri? Don’t even get me started. You talk a lot about this in the book, as we think of AI as this neutral space, but someone has programmed Siri and Alexa.”

Benjamin relayed the story of an acquaintance who worked for a tech giant designing digital assistants. This designer’s team considered all manners of dialects, accents, and vernaculars when programming the voice recognition mechanism, but not African American English. This designer sought answers.

“His supervisor said, ‘No, this is for a high-end market. We’re not doing that,’” Benjamin said. “This is an example of a design decision. It’s not that we’re technically unable to do it, it’s that in terms of the market viability and market identity of certain technologies, these judgement are made. So long as Blackness is seen as a lower-class aspect of marketing, then that’s not something that’s going to prioritized, even if they can.”

The conversation wove humor and personal anecdotes in with Benjamin’s explanation of her scholarship and vision. Benjamin revealed, to Johnson’s delight, her interest in theatre as a college student, and how her performance pursuits dovetailed well with her eventual majors in sociology and anthropology: in “the drama of life,” she said, and how the language of theatre is used to describe social roles. In the conversation and subsequent Q&A, she further outlined the work she does with Princeton’s Ida B. Wells Just Data Lab, which she founded, and a network of nonprofits that benefit from her research and mentorship. But perhaps the most significant takeaway was Benjamin’s reminder that technology’s ubiquity isn’t preordained. Users can and should, when necessary, just say no.

“I’m always trying to get us to think about these narratives we tell about technology,” she said. “There are two powerful stories: the one is the techno-dystopian story, where the robots are going to slay us, and take our jobs and our agency. The story from The Matrix, from Terminator. That’s the story that Hollywood wants to sell us.

“But the other story—and we should think about as a story—is the marketing of Silicon Valley—that the emerging technologies are going to save us. They’re going to make everything more efficient and more fair. We’re all just going to be able to play all day and not work. Although they seem like opposing stories, in that one has a happy ending and one has a sad ending, they share an underlying logic when you peel back the surface: they are assuming that technology is going to impact us, like we don’t have any agency, like it’s not human beings creating the negative or the positive. Part of what we need to constantly do is push back against this techno-deterministic notion… I encourage people not to just worry simply about technology itself, but look behind the screen, think about human agents and agencies that are actually trying to sell us these stories that technology is going to save us, because it’s not.”

The first “Dialogue” last fall featured John L. Jackson, the dean of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and codirector of Johnson’s documentary, Making Sweet Tea. The next event will feature UCLA’s Safiya Noble on April 22.

By Cara Lockwood and Kerry Trotter

Watch the “Dialogue” with Ruha Benjamin: